Anne Grunow loves to look at rocks, and feels fortunate that she is paid to do it. Like other geologists, she has studied maps, sketched rock formations, and collected, photographed, and then labeled many rock samples in her quest for understanding. Between 1982 and 1996, she logged a total of 12 trips to Antarctica, including both East and West Antarctica as well as the Antarctic Peninsula. In her current job as curator of the U.S. Polar Rock Repository (USPRR), she spends more of her days at a computer than “in the field.” Her work involves cataloging and recording specimens collected in both polar regions.

Researcher: Anne Grunow

University/Organization: U.S. Polar Rock Repository, Byrd Polar Research Center at The Ohio State University

Research Location: Antarctica and Columbus, Ohio

THE PUZZLE OF THE EARTH’S PAST

Anne Grunow’s primary research focus is plate tectonics. She works to better understand where the continent of Antarctica has been in the last one billion years by reading its history as recorded in its rocks. Interestingly enough, she was a history major in college until she took her first geology course. Anne says that she “fell in love with geology because it combined learning about the history of the earth with working outdoors.”

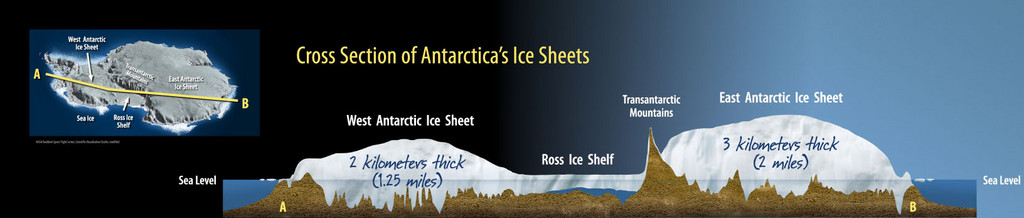

The geology of Antarctica is not well understood, because more than 98 percent of the landmass is covered by snow and ice (up to 5 kilometers, or 3.106 miles, thick). This certainly limits the areas where geologists can actually study the rock formations and gather samples. Rocks are more likely to be exposed near the coast along the margin of the ice sheet, along the Antarctic Peninsula, and farther inland where mountaintops protrude through the ice and snow. New technologies, like remote sensing, are being tested during the International Polar Year and may make it easier to get reliable information from the rocks beneath the great ice sheets of East Antarctica and West Antarctica.

Reconstructing the geological history of the continents is a lot like putting a giant jigsaw puzzle together. Scientists believe that earth’s landmasses have merged and separated repeatedly over time as supercontinents; that is, a continental mass significantly larger than any of today’s continents. While several supercontinents have existed in the earth’s 4.6-billion-year history, we are most familiar with the last supercontinent, Pangaea. This large landmass formed approximately 300 million years ago, and later broke into two sections: Laurentia and Gondwana (or Gondwanaland) about 200 million years ago.

Anne’s early work has contributed to the understanding of how and when Gondwana (which included Antarctica, South America, Africa, Madagascar, Australia-New Guinea, New Zealand, and the Indian subcontinent) broke up, approximately 167 million years ago. Antarctica later began to separate from the other continents, slowly drifting south to its present location.

While Antarctica appears to be one continent today, geologists understand that parts of the continent came together between 175 and 130 million years ago. The result is a geologically diverse continent, divided into East and West Antarctica and separated by the Transantarctic Mountains, which span the continent.

Anne’s research has helped scientists understand which parts of other continents collided with Antarctica to form West Antarctica. West Antarctica is composed of four microplates that merged approximately 180 million years ago.

“Ages before the Ice” 2002 map supplement about Antarctica. Used with permission from the National Geographic Society.

She has also studied the Transantarctic Mountains, which have an older history. They were formed approximately 500 million years ago – before Pangaea, when Gondwana first formed. Scientists have determined that the mountains were formed in part by the process of subduction, in which one plate is forced beneath another. Subduction zones are often accompanied by mountains, volcanic activity, and igneous rock. Geologic evidence of subduction in the Transantarctics includes the presence of granites and volcanism in the region.

Antarctica clearly has a long, complex geologic history. How do Anne and other scientists learn about events that happened millions of years ago?

MAGNETIC MINERALS

One of the tools that Anne uses is paleomagnetism, or the study of the record of earth’s magnetic field preserved in various magnetic minerals. Many rocks contain small magnetic crystals. When these rocks were formed, their magnetic crystals aligned themselves in accordance with earth’s magnetic field, much as a compass needle points toward the north magnetic pole. Scientists know that the locations of earth’s magnetic poles and the continents have changed throughout time, leading to differences in the position of these magnetic crystals in rocks of various ages.

The position of magnetic crystals in the rocks can thus help identify the position of the earth’s magnetic poles and the orientation of a rock formation to those poles when the rocks were being formed. As a result, scientists are able to describe the positions of the continents throughout geologic time, based on the orientation of the crystals and the age of the rocks they have identified.

BREAKING BARRIERS

Anne’s contributions to the field are significant not only in terms of scientific understanding but also in terms of equity in scientific research. She was the first woman to join an international remote-field expedition with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). This was in 1982, at a time when the British didn’t allow women to do field work in remote locations of Antarctica. Since it was an international expedition however, she joined the group and worked as a member of the team. She believes she was also the first and, in some cases, still the only woman to work in the outlying regions of the Ellsworth Mountains and in the Thurston Island/Pine Island Bay area of West Antarctica.

Anne’s fieldwork locations in Antarctica. Modified from an online map available from the Perry-Castaneda Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

There are probably only a handful of people who have traveled across more of the continent than Anne. This is partly because the focus of her research took her to the Transantarctic Mountains, including visits to outcrops of bedrock in South Victoria Land, Queen Maud Land, Thiel Mountain, and the Pensacola Mountains, via snowmobile or helicopter. She also explored the central region of West Antarctica, from the Ellsworth Mountains to Thurston Island, and along the Antarctic Peninsula aboard ship.

She has patches (cloth badges that can be stitched to a jacket) from 1985 to 1997 attesting to her work on the Polar Duke, the National Science Foundation’s research vessel that provided year-round support of Palmer Station on the Antarctica Peninsula. Anne also worked from various U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers. She has another patch pinned to her office wall that reads, “U.S. Antarctic Program, R/V Hero.” One might wonder, “Is that a recognition of the nature of her work, or the name of a ship?”

ADVENTURES IN THE FIELD

Many memorable moments are associated with Anne’s trips to Antarctica – like the time she and other researchers were helicoptered inland from a ship…and then the fog moved in. Since the helicopter couldn’t safely return to get them, they spent the night “on the ice,” making use of the survival gear that is required by the National Science Foundation for each person on a field outing. This is actually a fairly common experience. Anne remembers this particular occasion because a visiting official did not bring his survival gear that day. So one member of her team loaned him a sleeping bag for the night.

She also recalls a trip when a Twin Otter airplane broke a ski strut during a landing in the fog. The pilot taxied along the surface of the ice on the plane’s skis the entire distance back to the tent camp (about 5 miles). Every second of that time, the team members (and the pilot) were on edge, hoping they didn’t hit the deep cracks in the ice known as crevasses.

Anne often had to drive snowmobiles over crevassed areas to reach the rocks she wanted to study. “You’ll never forget the ‘whoosh’ sound that the snowmobile makes when it drops partly down into a crevasse as you’re traveling along!” she says. Fortunately, momentum always got her over the crevasse.

U.S. Polar Rock Repository

In 2003, Anne became curator of the U.S. Polar Rock Repository (USPRR), trading much of her time in the field for time spent organizing and cataloging rocks from the polar regions.

One of the advantages of studying rocks from Antarctica is that they include some of the oldest bedrock on earth and have been, for the most part, undisturbed by human activities. Since it opened in 2003, the repository has already amassed more than 15,000 specimens representing both polar regions.

Outreach is an important part of the USPRR’s work. Anne or her assistants frequently give talks to school groups and provide tours of the Repository, including an introduction to some of the tools that are used by geologists and the opportunity to try on some of the extreme cold weather gear. In the summer of 2006, a rock box was developed for loan to primary and intermediate grade teachers. It includes rock samples, tools and guides for identification, and curriculum materials developed by and for teachers. It is quite simple to borrow: Teachers complete an online request form, place a $50 deposit, and receive by mail a plywood box that has actually been used in one of the polar regions! The rock box comes with a return label and pre-paid postage. After the box is returned, the deposit is refunded.

Anne’s career as a geologist has allowed her to help piece together the history of the earth, studying details of magnetic features in rocks from a nearly inaccessible part of the world. In her fieldwork, sometimes under harsh conditions, she has experienced the thrill of discovery and the satisfaction of creating new understandings. Currently she is committed to building an archive that provides others with both a digital and a physical set of resources about rocks from the polar regions. She would like to return to Antarctica in the future. For now, she continues to be fully engaged, making polar geology available to anyone who wants to know more.

This article was written by Carol Landis. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site. The links on this page were updated on March 28, 2018.

Copyright September 2008 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.