For this month’s In the Field article, we are featuring Ross MacPhee, curator and researcher at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). This article is an excerpt from AMNH’s online BioBulletin. It provides a basic background on MacPhee’s research.

To view the entire bulletin, go to: http://www.amnh.org/sciencebulletins/biobulletin/biobulletin/story981.html.

To learn more, visit the Siberian Expedition: Wrangel Island web page. Listen to Ross MacPhee answer questions about mammals in our new podcast!

According to Ross MacPhee, chairman of the Department of Mammalogy of the American Museum of Natural History, mammoths should still be around. “If you gave ’em a shave, they’re very much like a modern elephant,” MacPhee points out. “These guys are incredibly buffered against extinction.”

MacPhee and colleagues have collected woolly mammoth remains on Siberia’s Wrangel Island, a 2000-square-mile island in the Chukchi Sea off northeastern Siberia. Woolly mammoths survived on Wrangel significantly longer than anywhere else on earth. The relative abundance and freshness of fossil remains made it the best place to start testing a theory about what killed them off.

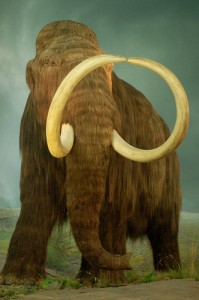

lA model of a mammoth. Photo courtesy of penmachine via Flickr.

Searching for Clues to Mammalian Extinctions

Only 11,000 years ago, as the glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age, hundreds of land-vertebrate species–including large mammals such as the woolly mammoth and the saber-toothed tiger–disappeared.

Theories as to what caused this great mammalian extinction event include climate change, overhunting by humans, or some combination of the two. But, according to Ross MacPhee, none of them add up.

MacPhee believes that the introduction of a new and highly lethal infection–a hyperdisease–could explain the particular characteristics of this strange extinction. And Wrangel was the best place on earth to look for evidence. “All other Mammuthus primigenius had become extinct by 10,000 years ago, but the population on Wrangel persisted an additional 6,000 years.

“Because Wrangel’s mammoths were such later survivors, we thought that if a deadly virus could be detected, their fossil remains would be the likeliest to have retained traces of it.”

Where Did the Hyperdisease Idea Come From?

“Like many ideas in science, the ‘hyperdisease hypothesis’ came about because of a casual, almost accidental juxtaposition of ideas that had, on the surface, nothing at all to do with one another,” says Ross MacPhee.

Remember when headlines announced that an asteroid impact caused the extinction of the dinosaurs? Even though this theory was widely popularized, not all scientists agree with it. They do agree that extinction, like evolution, is an integral part of the pattern of life on earth. The overwhelming majority of extinction events have occurred in clusters. But the factors which have caused most extinctions have yet to be determined.

Some of the oddest extinction events since the loss of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago have occurred during the last 50,000 years–that is, since the appearance of anatomically modern humans. During this time mammals had diversified and proliferated and included hundreds of species of megafauna–mammals weighing more than 100 pounds (44 kg). In the case of North America, near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch around 11,000 years ago, more than two thirds of the continent’s large mammals became extinct, apparently within the space of a few centuries.

Was It A One-Two Punch?

Some scientists think the losses can be attributed to a combination of factors that had different effects in different places. For example, overkill may have reduced the populations of certain species to the point that recovery was impossible, which seems to be happening with a number of endangered species in this century. Or, hunting activity might have overlapped with migration route or mating seasons in a devastating combination. Megaherbivores, like modern-day elephants, play a pivotal role in “opening up” forests for smaller grazers and browsers, and a crash in their populations could have rendered others vulnerable to extinction. But this is hard to prove on the basis of paleontological evidence, and MacPhee remains skeptical.

Or Was It Something Else Entirely?

“What else in nature, besides direct human impact, could have such a dramatic effect in such a short time?” wondered the scientist. “Why is it that again and again, all over the planet, I find the same story: that there’s really nothing happening until people come, and then the animals go down.” After reading a magazine article about the Ebola virus outbreak, MacPhee was struck by a sudden insight: the only thing capable of causing extinctions of this type and scale was a highly lethal infectious disease.

Digging into Ancient DNA

Finding numerous samples of well-preserved mammal remains is the first challenge, one of the reasons that MacPhee turned to Wrangel Island. Because Wrangel is a nature preserve, the American scientists agreed not to bring specimens back to the U.S. Instead, they carried drilled-out bone specimens for radiocarbon dating and molecular analysis. Each specimen is radiocarbon dated to make sure it coincides with the time of species extinction. Using the latest molecular biology techniques, these scientists are isolating the animal’s DNA. Once that has been accomplished, the final step is the search for “foreign” or “contaminant” DNA that could belong to the pathogen–the “smoking gun” of the hyperdisease theory.

Research Updates

Here are some updates from current research in this area:

Recently, scientists at Penn State report that they have sequenced the genome (genetic sequence) of the woolly mammoth. Comparing this genome with that of current-day African elephants will help to determine if the mammoth sequence has any potential contaminants from organisms such as bacteria or fungi.

MacPhee co-authored a study on native rats on Christmas Island in Australia that became extinct due to infectious hyperdisease. Black rats, invading from ships starting in 1899, came onto the island carrying fleas that served as a host for disease. The infection these fleas carried crossed over to native rats, killed their population, and rendered them extinct by 1908.

In 2007, a reindeer hunter discovered a baby mammoth preserved in the permafrost of the Russian Arctic. Here’s a short video showing the baby mammoth.

Located in Hot Springs, South Dakota, the Mammoth Site is the world’s largest Columbian (North American) mammoth research facility with ongoing research, educational resources, and a virtual tour.

Dr. MacPhee also agreed to answer our questions about mammals. Learn about mammal characteristics, adaptations, and polar mammals in “What Is a Mammal? Answers from Ross MacPhee.” Also, you can hear excerpts from our interview in our new Polar Podcast.

Polar Podcasts: Mammals

Listen to excerpts from our interview with Ross MacPhee and learn about highlights from our magazine and blog in this podcast. Our new monthly podcast series is also available on the NSDL section of iTunes U: Beyond Campus.

This article was adapted by Robert Payo from a special feature from the American Museum of Natural History. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright January 2009 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.