Popular culture is a 24/7 stream of information broadcast through TVs, cell phones, music players, movies, radios, and over the Internet. Its messages inform how we spend, speak, learn, dress, communicate, relate to one another, and form opinions. This constant stream is not all fluff. Teachable science and learning concepts emerge when serious ideas make the news, even if the ideas are part of a controversy or coverage of a celebrity. In this column, we investigate popular culture offerings about the Arctic and Antarctic regions to give teachers background information to inspire critical classroom discussion and thinking based on entertainment and news media that students are exposed to outside the classroom.

Long before cyberfiction, online gaming, digital photography, and long-distance jet travel were part of daily life, people read news accounts of surprising phenomena, great voyages, and brave exploits with the same kind curiosity and awe now reserved for the next big box-office hit. Newspaper articles from the 19th century were expected to both enlighten and entertain. While early stories of polar survival may not seem hard-hitting by today’s action-adventure standards, a New York Times overview of 300 years of efforts to explore the North Pole, published on September 2, 1909, offered readers nail-biting highlights from accounts of 578 polar expeditions initiated from 1800-1900.

The article suggests that the reason for more polar exploration to the north rather than to the South Pole was due to the proximity of northern routes to European and North American ports, coupled with commercial companies’ interest in finding a northwest passage through the Arctic to establish a direct route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The 1909 New York Times overview reported “a series of Arctic tragedies” as one adventurer after another set off to find fellow explorers lost in the arctic regions, and to discover uncharted waters along the way, often at great personal sacrifice:

Perhaps no better picture of terrors of the arctic and its stabbing cold can be found than that which is given by Mr. Melville, [U.S. Navy engineer, commander of an 1881 expedition to look for remains of the DeLong expedition]: “A cold, barren plateau, between a small outlying promontory and a bleak weather-riven rock of red syenite reaching to the skies, on which even the mosses and lichens would scarce grow. The raging of the wind and the pitiless sea, and the roar of the black water of the bay dashing over the ice-foot, made the lonesome picture look colder and more appalling. Drifts of ice and snow choked the ravines and hollows; but, saving ourselves and the famished, skeleton-like survivors, not a living thing appeared on the whitened landscape.

It’s no wonder that early science-fiction writers like Jules Verne (1828-1905), who came of age reading Arctic adventure reports, were inspired to create works of popular fiction based on the grisly details of early polar exploration.

A recent translation by William Butcher of Jules Verne’s second novel, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1866), recounts a fictitious voyage to the top of the world complete with disloyal crew, an ice-bound ship, human tragedy, and short supplies. The original manuscript was published in France as part of Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages series by Pierre-Jules Hetze, which included classics such as Around the World in 80 Days. “Hatteras” was preceded by Verne’s first polar adventure book titled Wintering in the Ice (1855).

Verne’s fiction was prized for both its fantasy and its nuts and bolts descriptions of natural and often invented phenomena. The Adventures of Captain Hatteras begins in 1860 as the reader is caught up in elaborate and detailed preparations for an unknown journey that neither the commander nor the crew fully understands. There is an absent captain who delivers instructions to second-in-command Richard Shandon for the design, building, and outfitting of the vessel Forward, that strongly suggest a voyage to Northern seas. The characters’ growing fear of their unknown destination, missing captain, and questionable mission adds to the tension as the Forward embarks from the Liverpool docks.

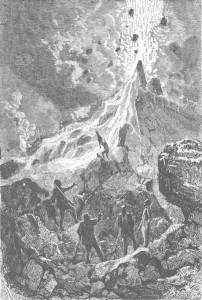

The volcano at the North Pole from the original publication of Journeys and Adventures of Captain Hatteras by Jules Verne. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The story offers details about food, clothing, and gear, along with instructions for how to load enough stores on a ship to last for several years. These descriptions lie in stark contrast to modern outfitting for cold weather. Instead of hi-tech fleece layers, down sleeping bags guaranteed to minus 25 degrees Fahrenheit, and thermal footwear, early explorers wore “sealskins” and knew that there were no guarantees of protection against extreme cold and hardship. The crew members’ knowledge of sailors who had headed north never to return makes their commitment to the Forward seem even more dramatic as the vessel slips through each degree of northern latitude. As they battle their way through ice-clogged seas, their fatigue and frustration with their unknown journey grows in proportion to their dislike of their absent captain, who appears to be playing with their lives.

In this way Verne skillfully sets the stage for later perils and death-defying feats of survival called “motifs of death, blood, and ice” by translator William Butcher. Hatteras skillfully weaves day-to-day feats of survival on a typical 19th century arctic voyage against a backdrop of interpersonal conflict and deceit. The dramatic value of this early popular work of fiction easily compares to current film or video game narrative action, while at the same time offering classroom opportunities for comparing historic Arctic voyages of discovery with current polar exploration goals and practices.

This article was written by Carol Minton Morris. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright April 2008 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.