As part of their jobs at a university library, Gerrit Vyn and Martha Fischer’s duties include field expeditions to remote polar regions to gather original materials to archive. That’s because Gerrit and Martha don’t work at a book library; they work at the world’s largest scientific archive of recordings of the behaviors of animals. Gerrit and Martha are sound recordists, and in June 2008, they went on expedition in Nunavut, Canada, to capture the sounds of wildlife.

Researchers: Gerrit Vyn and Martha Fischer

University/Organization: Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Macaulay Library

Research Location: Bathurst Island, Nunavut, Canada, and Ithaca, New York

Listen to some of the recordings from this expedition in this month’s podcast!

PREPARING FOR WINTER IN JUNE

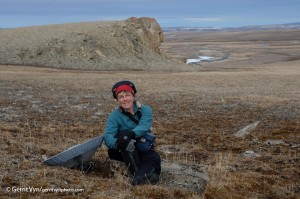

Last summer, just when it started to get nice in central New York, Gerrit Vyn and Martha Fischer did something unusual. They packed up enough food for three weeks and headed to an uninhabited island above the Arctic Circle, to camp out in 30-degree weather and constant sunlight. The purpose of their trip was to record animal sounds, and in particular, the vocalizations of a male sanderling (a small sandpiper) in mating flight display. Gerrit and Martha work for the Macaulay Library, an archive at Cornell University devoted to collecting, permanently preserving, and providing access to an audio and video record of the behaviors of animals.

I spoke with Gerrit and Martha just before they left, about the purpose of the trip, their goals, their training, and what they thought it might be like. Although both were a bit nervous about the unknown, their previous training and expeditions to record sounds in other remote locations, like the Alaskan tundra (Gerrit) and the cliffs of Newfoundland (Martha), served them in good stead in preparing for this adventure.

About the Researchers

Gerrit hails from Detroit and has a background as a field biologist in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. He previously worked in southern Africa as a Peace Corp volunteer and director of a conservation organization. He has worked at the Macaulay Library and Cornell Lab of Ornithology since 2004 as an audio production engineer. In his spare time, he is a freelance photographer, and enjoys playing banjo and singing in a bluegrass band. He previously directed Alaska recording expeditions in 2006-2007 to capture the sounds of the tundra in areas at risk of noise from future oil drilling. Listen to interviews on Living on Earth and Bird Note, or read his article Tundra Trek in Living Bird.

Martha was raised in small-town Ohio, and has had a lifelong interest in birds and nature (“I knew I wanted to be an ornithologist in fourth grade,” she says). She came to the Lab of Ornithology in 1993, working in a variety of capacities in the education program, such as coordinating a citizen science effort called Project PigeonWatch, answering questions from the public, editing the Citizen’s Guide to Migratory Bird Conservation, and coordinating the first International Migratory Bird Day celebration.

In 1997, Martha moved to her current position as a terrestrial audio archivist, where she records, archives, and annotates the sounds of birds, insects, and frogs. She previously directed a 2007 expedition to Newfoundland to record the sounds of cliff-nesting seabirds and forest-dwelling songbirds. Due to her patient nature and good sense of humor, she is often in demand to help lead recording workshops, train scientists borrowing equipment, and work with recordists on return from their trips to promptly and accurately archive their sounds.

What was the purpose of this trip?

The Macaulay Library serves as a permanent archive for scientists, educators, and others who need access to a diverse and authenticated collection of animal sounds from around the globe. For the last year or so, thanks to the generosity of an anonymous donor, Macaulay Library staff have been engaged in a systematic effort to capture all of the major behavioral displays of all North American species of birds (their vocalizations, feeding behavior, courtship, nesting, and flight). Many of the shorebirds we know from trips to the beach, such as the sanderling, a tiny sandpiper often seen in small groups chasing ocean waves, migrate long distances to breed in the high Arctic. Few people have even seen, let alone photographed or recorded, their nesting and chick-rearing behavior. The Macaulay Library’s previous recordings of sandpipers from Nunavut and the Northwest Territories (as well as various buntings, plovers, larks, and longspurs) mainly date to a single expedition in the 1960s.

Gerrit and Martha’s expedition was a bit different from some of work described in this column since their goal was not to conduct a study to test a hypothesis. The main purpose of their trip was to collect specimens, in this case as many high quality sounds of diverse behaviors from target species as possible. Before they left, Gerrit listed some of the target species they were trying to record: sanderlings, red knots, purple sandpipers, white-rumped sandpipers, Baird’s sandpipers, as well as king eiders, snowy owls, and pomarine jaegar. He anticipated that they might encounter mammals such as lemmings, musk ox, wolves, and caribou.

Getting to Bathurst Island

Gerrit and Martha’s travels involved flying from Ottawa to Iqaluit to Resolute Bay, the farthest north one can fly on commercial airlines, and one of the coldest inhabited places in the world. After brief forays around the old town dump on foot and by “bike” (really an ATV with a wagon attached to carry gear) to record purple sandpipers, Gerrit and Martha continued by small plane to Bathurst Island.

Bathurst Island, located above the Arctic Circle and approximately 250 miles from the magnetic north pole, is surrounded by ice. Bathurst has no trees and no permanent inhabitants. Martha and Gerrit set up tents near a small research station housing hydrologists from York University in Ontario.”The landscape feels immense,” Gerrit said, “like being dropped off on the moon.”

What do sound recordists do?

With the 24-hour sunlight, the recordists didn’t need to bring a flashlight, but they did bring a shotgun for safety in case of unexpected encounters with polar bears. Their gear included digital sound recorders, like the Nagra Ares BB+, a compact solid-state recorder capable of capturing nearly 15 hours of high-quality, uncompressed .wav files. Their microphones included omni-directional shotgun microphones with fuzzy windscreens, a stereo remote microphone setup, and a parabola for focused recordings of single individuals with little background noise.

Sound recording can be exhausting work. Successful recordists must be able to get up early (or hardly sleep when the daylight stretches on indefinitely) and walk long distances over all kinds of ground carrying gear. They must also have large amounts of patience and the ability to stand still with their arm extended out for long periods of time, ignoring such hazards as wet feet and biting insects. One of the greatest impediments to a sound recordist’s work is wind noise. In their recorded trip updates, Gerrit and Martha often described waiting up to 36 hours straight for heavy winds to die down.

Gerrit and Martha had trouble focusing on capturing the other wildlife diversity until they knew whether they would be likely to capture the sanderling male’s breeding display sounds. They worried that they came too late in the breeding season, and that most of the birds seemed to be paired up already. Despite this, they made the most of the constant daylight hours to record when it was calm enough, and did reconnaissance for nests when it was too windy. They managed to record most of the sandpiper species they were aiming for, including the purple sandpiper, as well as rock ptarmigans, snow geese, and king eiders. They also recorded some other species not well-represented in the archive, such as the long-tailed jaegar.

Gerrit and Martha made the most of one windy day by leaving their recording gear and hiking nearly 10 miles, stopping to scan with binoculars for birds and nesting areas, and marking GPS points to return to later under better recording conditions. Although they walked far apart, Martha said, “It’s so big and wide open that it seems like it would be hard to get lost. But still…you have to be careful…keep your wits about you and your eye on various landmarks. There’s some large rock outcroppings that help.” When the wind eventually died down, Martha and Gerrit both described the silence as one of the most profound they had ever heard, broken only by occasional bird sounds.

The wind isn’t the only challenge for a recordist, however. Even with the shock-mounts used with most recorders, handling noise is always a concern. Stepping into the field with recording gear gives you an immediate awareness of your every noise, from breathing and rustling clothes to crunching footsteps. While working, Martha and Gerrit often spread out as much as half a mile apart, to avoid tramping into and spoiling each other’s audio specimens. Sometimes they combined forces as well. For example, when Gerrit used an iPod and portable speakers to play back sounds to a white-rumped sandpiper, Martha recorded it responding. When Gerrit was recording a pair of sanderlings, Martha was able to alert him to the approach of a third bird as it came up and interacted with the pair.

A highlight of the expedition was capturing both audio and video of snowy owls around the nest. After they came across the nest, Martha and Gerrit carefully set up a blind. They then ran cables out to a remote microphone set up with stereo sound. Their patience eventually paid off when they were able to capture recordings of the male snowy owl bringing prey (in this case a lemming) to the nest and of the female feeding lemming to her chicks. Finally, near the end of the trip, Gerrit and Martha heard a male sanderling displaying right by their tent, and Gerrit ran out in the rain to capture a recording (complete with the sound of rain on the reflector). Later they were able to get another recording in clearer weather, making the trip a success from the standpoint of that badly needed specimen.

Bathurst Island, Canadian Arctic – Images by Gerrit Vyn

What is the Macaulay Library?

Through field notes or even annotations directly on the recordings, Martha and Gerrit use their biology and ornithology backgrounds to identify the species and behaviors of the animals they are recording, greatly increasing the value of these specimens for others who will eventually use them. When back in Ithaca, Martha will archive their specimens using software such as SonicStudio for the Macintosh, entering into the Macaulay Library database as many different fields of annotation as possible (GPS location, time, date, habitat, as well as number, age, sex, and behaviors of the subjects).

Gerrit, a member of the media distribution team, works with clients to find and deliver examples of species and behaviors for use in radio programs and products like toys and audio books. He also produces authoritative audio guides of recordings specific to a certain geographic area or group of organisms, such as the two-CD collection Voices of North American Owls. For that project, Gerrit worked with external recordists and collected his own specimens, including high-quality photographs for the booklet, and edited and mastered the production with other engineers in the Macaulay Library’s studios.

Thanks to funding from the National Science Digital Library, created by the National Science Foundation, a majority of Macaulay Library specimens have been digitized and are available as a resource to anyone with an Internet connection. You can browse, listen, and learn more about recording and archiving techniques at: www.birds.cornell.edu/macaulaylibrary.

This article was written by Colleen McLinn. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright February 2009 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.

Images and slide show are not covered under the Creative Commons license.