It sounds a bit like the tent is going to rip apart anytime. I smile reassuringly to my tent partner, Mikkel. It is his first time – and he is appreciating firsthand the immense strength of our tunnel tents. Made in Sweden, they are constructed of four arches with buttresses at the base on the principle of the Sámi goathi, the traditional dwellings of the Arctic peoples of Scandinavia. If an arch is rotated 360 degrees in a circle, it becomes a strong, three-dimensional, symmetrical shape – a dome, like that of an igloo, the traditional dwelling of the Inuit people during winter here on Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada, where our tent is pitched right now.

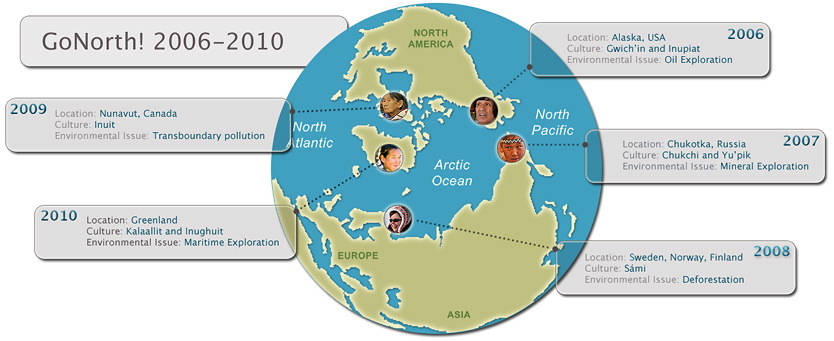

We are in the field delivering GoNorth! Nunavut 2009, the fourth annual program in the GoNorth! adventure learning series focused on the circumpolar Arctic and environmental issues of global concern. As always, our Arctic locale and its indigenous people is the springboard for the live program, and this year our focus, as well as that of the K-12 students in more than 4,500 schools, is transboundary pollution. It has once again been an incredible journey – live from the field with students in more than 30 countries worldwide. We have worked with scientists in Pangnirtung catching Greenlandic sharks to check their brains for mercury content; we have marveled at Baffin’s teens who mash-up urban hip-hop with traditional Inuit dances and games; and on a rather horrifying note, we can say for the first time ever we experienced the effect of climate change firsthand as the mighty Polar Husky sled dogs miraculously pulled us across an exploding mess of gigantic boulders and raining rocks barely held together by melting permafrost through the Akshayuk Pass in the Auyuittuq National Park.

Now sitting on a hillside by the shore of the Arctic Ocean, we are maybe a day by dogsled from Clyde River – the end of the adventures until we head for Greenland next year. Once the ground blizzard lifts, that is. We will be fine though, as long as the tent is aligned with the 40- to 50-mile-an-hour winds whipping from the south.

| In Inuktitut, the language of the Canadian Inuit Auyuittuq means “the land that never melts” and more than 100 glaciers stretch out from the Penny Ice cap in the glacier-scoured terrain of jagged mountains here. Last summer the eternal ice that dammed up the glacial lake at the very top of the pass, Summit Lake, came unplugged. A monstrous flash flood tore through the pass undercutting banks already fragile from melting permafrost, shoving boulders around like peas in a pot and in effect eliminating what has been the traditional route to safely cross over the spine of Baffin Island. Read on about the pass in the weekly trail report Wild.

Watch A Tunnel Tent: Its “Arctic design” in action in this small ground blizzard! Check out the lesson Home Sturdy Home to explore traditional knowledge of Arctic people such as the Sámi while experiencing the strength of arches. Hear how a 2nd grade teacher in California used the lesson with her students! |

Mikkel is careful not to ask me any questions about the wind. I never talk about wind on the trail. I was 19 when I started traveling in the circumpolar Arctic by dog team every year. It has been 17 years learning to be utterly humble: Call me crazy, but I am not showing disrespect to the winds by talking as if I know what they are up to! The traditional belief of the Canadian Inuit people is that this wind from east-southeast direction, Nigiq, is a man. It blows steadily, creating flat, even snowscapes. Opposite him, from west-northwest, is a woman, Uangnaq. The two do not get along all that well, and are said to retaliate against each other. She blows at an uneven pace, creating strong drifts with a tip that resembles a tongue. When dog sledding, we stay oriented by looking to the shape and form of the snowdrifts created by the prevailing winds, the sastrugi. Even the lead dog uses it to keep bearing.

Of course, we are also helped by modern means, such as GPS, just like the Inuit hunters in Nunavut we meet out on the land on their snowmobiles to hunt; but as important even today are traditional navigational tools like prevailing winds, sastrugi, landmarks, the rising and setting of the sun, animal migration patterns, constellations, and stars.

Check out the lesson Stargazing that sets out to explore use of stars and constellations in navigation as an example of traditional knowledge used in practice in the GoNorth! Curriculum and Activity Guide 2009. |

The online learning environment at PolarHusky.com brings the learning and adventure together, motivating your students to have fun learning – even the youngest ones: go stargazing in Wumpa’s World! |

The North Star, the Pole Star, Polaris, always sits above the earth’s magnetic north where it appears to be circled by all other stars and constellations – a trick of earth’s rotation. The Kaalallit in Greenland have named the North Star Nuuttuittuq, which means “never moves.” The Sámi people call it Davvenásti, “Pillar of the World,” much like the the Chukchi of Chukotka call it Unp-e’ner, “the Pole Stuck Star,” both after the tether pole that reindeer circle. Seemingly attached to the North Star are the circumpolar or Arctic constellations, visible all year in the Northern Hemisphere. In western astronomy the main circumpolar constellations are known as Ursa Major (the Great Bear), Ursa Minor (the Little Bear, the Little Dipper), Draco (the Dragon), Cepheus (the King) and Cassiopepeia (the Queen). How they are known to indigenous people in the Arctic – well, that all depends on what Arctic peoples!

Arctic Peoples: Who Are They, Anyway?

Contrary to the widely accepted idea that Arctic peoples have strikingly similar physical characteristics and cultures, the about 400,000 indigenous people that live in the circumpolar north are of very diverse indigenous groups: The Gwich’in and Dene in North America, the Sámi in northern Fennoscandia and into the Kola Peninsula in Russia along with a dozen or so other ethnic groups in northern Russia, including the Nenets, Chukchi and Yupik. An Inuit people, the Yup’ik, are on both sides of the Bering Strait that separates Asia from North America. All once known as Eskimo, a term no longer used in most regions, Inuit is a broad label to describe the Arctic peoples that speak related languages or dialects in the Eskimo-Aleut language. Spanning from the Inupiat in northern Alaska to the Kalaallit in Greenland, Inuit total about 155,000 in Arctic Alaska, Canada, Russia and Greenland.

What the cultures of all these Arctic peoples share is that they are keenly adapted to the demanding Arctic environment.

The Caribou People

Alaska’s North Slope, encompassing the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), is one of the most extreme environments in which humans live and work. The average temperatures are too low to grow timber or food. To the Native people of the communities, the Gwich’in and the Inupiat, the means for survival have been, and to a large extent still are, hunting and gathering. Cultural knowledge and practices have been refined over many generations in an environment where one poor decision can lead to the death or starvation of an entire village.

Living on the coast, the Inupiat traditionally rely on sea mammals, whereas the Gwich’in, living in the forested areas, rely primarily on the caribou. Records indicate caribou have been hunted in the ANWR some 30,000 years!

In their own language, Gwich’in means “people of the caribou.” More than a life-sustaining resource, the animals are also an important spiritual component of Gwich’in lives. The traditional belief is that “every caribou has a bit of the human heart in him, and every human has a bit of caribou heart.” Arctic peoples view themselves as part of the environment and not separate from it, and reverence for the environment and its inhabitants underlies their cultures.

|

Listen to hunter Charlie Swaney talk about the caribou hunt and how important it is for all. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com |

Caribou is the primary food staple for the remote Arctic Gwich’in communities. Store-bought food is high-priced. The cooperative (the Co-op) in Arctic Village sells a chicken for $11.50 per pound and beef at $14.50 per pound (2006 prices). Low incomes make purchasing these protein sources difficult and high-quality caribou meat, containing little fat and more protein per pound than beef, pork, or chicken, is highly valued. It is possible to keep a balanced diet simply by eating caribou; the meat is rich in vitamin C (caribou eat lots of lichen!) and the organs provide a range of vitamins and minerals. After a hunt, sharing the meat with other community members strengthens social ties and promotes respect and caring for Elders.

Gwich’in rely on the land and the caribou, with more than 75 percent of their resources obtained from hunting and gathering. Baseball caps and jeans are everywhere, but so are winter boots, slippers, socks, purses, bags, and shirts made from caribou skins. Based on traditional designs, clothing, footwear, bags, and wall hangings are elaborately decorated with caribou hair tufting, and embroidery with plastic beads or porcupine quills colorfully dyed and woven into flower, animal, and geometric patterns. Much of this, as well as bone and antler carved into ornaments and jewelry, is shipped out to be sold to Alaskan tourists.

|

Watch students discuss what they do for fun in the Gwich’in community of Arctic Village. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

Check out these lessons:The Man Who Became CaribouPage 14: explore how Gwich’in value caribou in music, stories and arts.Caribou HuntPage 16: explore subsistence hunting as food source and the value of harvesting to ensure healthy animal populations. Visit Life in Kaktovika blog created for the GoNorth! community by Arctic ‘expert students’ in 5th and 6th grade. Kaktovik is an Inupiat whaling community on the coastal plain of ANWR and the Arctic Coast.Explore more about Gwich’in and the Inupiat Inuit along the coast of Alaska with the adventure learning expedition: GoNorth! ANWR 2006 |

Sense of Place (It’s all in the eye of the beholder)

Like the Gwich’in, to all Arctic peoples their homeland, the land and the sea and its animals, is much more than a place of resources – it defines “sense of self.”

Environmental scientists have classified the various regions of the Arctic into zones, based on the climate and geology of each region. Arctic peoples have their own classifications. For example, the Sámi notion of the reindeer forest includes what scientists would call woodlands, tundra and mountains – the term simply refers to anywhere that the work of reindeer herding takes place. Other designations for the land change seasonally. The same patch of earth might be called mustikassa during the blueberry season and lintumetsa, or bird forest, at another time of the year. Another traditional Sámi classification of the land is based upon sieidi (or seitas), sacred natural places with a ritual or even supernatural significance.

In the traditional worldview of Arctic peoples, all aspects of the natural world – animals, lakes, rivers, the sun, the moon, the winds – have souls just like humans. An Inuit hunter asks a seal’s forgiveness for killing it, and by giving it water, returns its soul safely to the spirit world and Sedna, the Sea Woman, who together with Moon Man balances the world – the cycles of the moon determine the seasons, and the seasons determine the availability of game.

|

A seal to be used for the week’s school lunch is carried into the school in Pangnirtung on Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. Check out the lesson Talking Culture to explore the relationship of food to cultural identity and how it is connected to a place. |

‘On the trail’ we meet an Inuit hunter returning from a successful hunt on the land. Sharing the harvest is an all-important aspect of Arctic peoples culture. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. Watch the movie Cold Cuts – Cuisine of the Arctic and check out the lesson Foods in Fashion exploring the basic elements of healthy nutrition and its relationship to food and culture. |

Hunting seal and caribou, Inuit in Canada traditionally base their lifestyle around following the seasons and the migrations of animals, in the past moving between summer and winter camps. To the Canadian Inuit it was as late as the 1950s and 1960s that they moved – some willingly, some under compulsion – into settled communities created by the Canadian government, most often around a missionary station by the Hudson Bay trading post, first established in 1670. In much of the Arctic, prolonged contact with Europeans began when whalers entered the region in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Once the whaling industry started to decline in the late 1800s it was replaced by the European and North American quest for furs. This created a shift in the seasonal use of the land; in the Russian, Canadian, and Alaskan Arctic, it put Arctic peoples in direct and continuing economic relationship with fur-trading companies. By the 1950s the Canadian government was on a mission to establish a presence throughout the Canadian Arctic and to assimilate the Inuit into the mainstream economic, social, and cultural life of Canada. The Inuit were believed to be living on the edge of starvation in a barren inhospitable wilderness. The indigenous inhabitants of the Arctic were to be become modern Canadians, able to improve their lifestyle options and take their place in the new period of economic development on the Canadian Arctic frontier!

Traditional Knowledge – It’s a Matter of Survival!

Indeed, in spite of their rich cultural heritage, Arctic peoples and their culture have long been treated as inferior. Early Euro-American visitors to the Arctic were lured by the promise of riches from whale oil, ivory and baleen and by prestige in the heyday of Arctic exploration. They brought with them exotic trade items, new materials, technologies and ideas – as well as diseases, exploitation and colonial domination. Colonizing governments claimed native territories as their own, often enforcing their tenancy with brutality and imposing new customs and religions. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak Native languages, and often sent to faraway boarding schools to be “reeducated” in non-Native ways.

|

May 1st celebration in Laverentiya – the closest community to the US in Russia. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

Pigs feet in the store freezer in Arctic Chukotka! Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

During the 1920s Lenin and other Bolsheviks argued that the Native peoples and minorities of the Soviet empire should be assimilated into the political, cultural and economic mainstream of the country; even remote peoples, such as the Chukchi and Yup’ik living far from Moscow in Chukotka, a vast Russian territory in the far northeastern corner of Asia, did not escape the dramatic upheavals under Stalin.

During the Soviet era, Chukchi and Yup’ik were organized together in territorial administrative groups known as oblasts and were settled into permanent coastal villages or collective farms. New economic activities were introduced, including factories to make pork sausages and growing cucumbers in hot spring-powered greenhouses! Traditional nomadic subsistence living – Chukchi reindeer herding, and Yu’pik maritime hunting – underwent structural collectivization. Families would no longer travel together following the seasons of the land and the migration of animals. Men and women were separated to handle different niches, while children were sent away to boarding school. The traditional social structure and family unit were lost along with the transferring of traditional knowledge and skills. Moreover, the strong Native ties across the Bering Strait were severed. The region is separated from the United States in places by only a sliver of water less than 80 miles wide. As a result, Chukotka was a military zone packed with troops and entirely closed to outsiders (even Russians) for close to 75 years – except for Gulag prisoners who toiled in gold and lead mines.

|

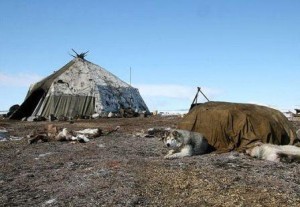

Visiting with reindeer herders in their yaranga camp on the tundra in Chukotka. One yaranga is made from 50-70 reindeer skins.Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

GoNorth! team member Aaron Doering inside the dark sleeping quarters of the yaranga – heated with the traditional lamps using seal oil. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. Watch video of inside the yarange with Chukichi reindeer herders. |

A quagmire of environmental problems such as pollution and large-scale resource development amassed for the Native people of Chukotka to inherit as the Soviet Union dissolved. Worst, the abrupt collapse of the Soviet Union left them in a state of a humanitarian catastrophe: Still repressed by the former KGB, the Native people were now cut off from western Russia and essential supply lines. By winter of 2001, there were literally no food provisions and no oil in the communities for heating or powering of machinery. While stripped of traditional knowledge, the Natives found themselves having to rely on traditional subsistence activities for their survival. Local hunters who had not harvested whales for years had no choice but to resume whaling, despite inadequate equipment, knowledge and skills required for safe and successful hunting. However, the Cold War coming to an end, Yu’pik were again able embrace their friends and family ties across the Strait, and hunters from Alaska’s North Slope traveled to Chukotka in 2002 with motors for small boats and other supplies and, most important, shared traditional whaling skills. Today, marine mammal hunting has become vital to Yup’ik and Chukchi coastal communities again.

|

Watch 5th grade teacher Jeff Sipper talk about his experiences on the trail as Teacher Explorer 2007 traveling with Team GoNorth! in Cukotka, Russia. Check out the lesson Walrus Web exploring how Natives’ subsistence is related to the food web and the consequences of change! |

Explore Chukotka with GoNorth! Chukotka 2007. |

Breaking the Beat: A Broken Record

Today Chukotka’s Arctic people are also reclaiming important aspects of their culture, including language and religious practices. Authorities repressed their languages and outlawed shamanism. The cultures of all Arctic people are rooted in an oral tradition: Knowledge and history survived in songs, stories and legends passed on from one generation to the next in the dark winter evenings, accompanied by chants and the rhythm of the drum.

The drum holds a special role throughout the entire Arctic region. From about 3 feet in diameter in north-eastern Russia, western Canada and Alaska to the small drum of the Polar Inuit in Greenland, the round ring is covered with skin from the stomach of a bear, walrus or reindeer and fixed with a round handle often decorated with a little carved face. The availability of wood in the area determined the size of the drum. Traditionally Greenlandic Polar Inuit made the ring by joining pieces of bone or reindeer antler, while the Sámi, being in a region with plenty wood below the tree-line in Scandinavia, construct the most elaborate drums. Their Runebomme could be either an oval ring or even a wooden bowl with two or more oblong holes as handles and beaten with a Y-shaped stick made of reindeer antler. Unlike the drums of the Inuit people, theirs were richly painted with figures, believed to be maps of the spiritual world for the noaidi—the Sámi shaman. The chant, yoiking, accompanying the drums is also quite different in sound from that of other Arctic peoples such as the throat singing of Inupiat, Yup’ik, Chukchi and Kalaallit in Greenland.

| Watch the throat song and drum dance Sandhill Cranes with youngsters in Chukotka.

Listen to a Sámi Yoik. |

|

Like the shamans, the drums and the chanting were “evils” to western missionaries. In Scandinavia, by the seventeenth century, Sámi shamans were put on trial for practicing witchcraft, and a ruling of the Danish king outlawed Sámi yoiking. The voice of the Sámi was silenced and drums were gathered up and burned, leaving only 70 traditional drums known to exist today.

The Right to Be (Indigenous)

The oldest inhabitants of the European continent, ancestors of Sámi, are believed to have been the first to push their way into the northern lands of Fennoscandia after the last Ice Age, 10,000 B.C., when the inland ice receded in northern Scandinavia; just as it is believed that the first immigrants came to North America from Siberia, by way of Chukotka, across the Bering land bridge, a narrow strip of land exposed by low sea levels at the same time. Some thousand years later, these ancestors of the Inuit made their way into Canada and finally onto Greenland.

From long before national boundaries, Sápmi, the natural territory of the Sámi, overlaps within four nations: Sweden, Norway, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The Sámi culture encompasses many lifestyles, from woodland hunter-gatherers to seafaring fishermen. Over the past 2,000 years or more, the Sámi identity became closely intertwined with the cultural practice of reindeer husbandry. The reindeer remains a potent part of the thriving Sámi identity though only a fraction of the Sámi people today (some 3,000 out of a population of 70,000 or more) depends on husbandry for their livelihood.

At the reindeer races in Inari! Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

Explore Sámi and the land of Sápmi with GoNorth! Fennoscandia 2008. |

At various points in history, Sámi have been burned at the stake because of their religious beliefs, prohibited from speaking their own language, and stripped of their traditional garments. By the yardstick of modern notions of human rights, it is no exaggeration to say that their experience has been one of complete and total annihilation of freedom of expression. By the last decades of the nineteenth century, policy against Sámi was influenced by racial biology: it was believed that the Sámi were born with certain characteristics that prohibited them from living as “civilized” people. In Sweden, under the Nomad School Act of 1913, Sámi children were denied admission to public schools. Instead, to limit the Sámi’s education and ensure that they not become “civilized,” during the summer teachers traveled to teach young students in their family’s tents for a few weeks. From this time and 40-50 years forward, most Sámi pretended not to be Sámi at all.

|

How we play reflects the identity of our people! Walking into a little store in Kiruna in Sweden to buy some traditional reindeer sausage for the trail, I fall in love with a doll dressed in the traditional Sámi garment kolt or gákti in the same colors as in the Sámi flag: red, green, blue and yellow colors-what the Sámi say are the colors of nature. Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

Make a traditional Sámi Four Winds Hat with your students! The lesson Hat Tricks explores how play, objects and clothing reflect culture while practicing pattern recognition and geometry through Sámi decoration.Watch Playing Culture – Sámi students playing house in a levi, a traditional dwelling Sámi use when living on the land.Watch Duodji – Sámi crafts and tools. Why are “things” so important to us?Listen to Growing up Sámi with Nils at Samediggi in Kiruna, Sweden. |

However, for the past 30 years Sámi have been at the forefront of reclaiming their identity and rights – and that of Native people across the globe. In the Scandinavian countries, Sámi have decision-making powers on matters such as Sámi culture, language and schools. The Sámi community and outstanding members such as Ole Henrik Magga have been instrumental in making the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. More than 22 years in the making, it details the rights to self-determination for the Sámi and other indigenous populations. Ratified by 140-some countries, the declaration is instrumental to the progress in indigenous peoples’ right to ownership of land and water and to cultural and language preservation worldwide.

Our Land

While the Sámi laid the path for self-determination, the circumpolar Arctic peoples are looking to Greenland to lead. The 57,000 Greenlanders are the first Arctic peoples to achieve self-determination and self-government. Home rule was introduced in Greenland in 1979 when legislative power was transferred from the Danish parliament to the Greenlandic Home Rule parliament, and the country officially was named Kalaallit Nunaat, “the Greenlanders Land.” Anxious about hunting and fishing rights, one of the Greenlanders first actions was to promptly vote to pull themselves out of the European Union (then the European Community).

Three indigenous groups live in Greenland, the world’s largest island: the Kalaallit, the Inughuit (Polar Inuit, the world’s most northerly indigenous people), and the Iit. Greenland was regarded a part of Danish-Norwegian territory since the independent Norse medieval communities that arrived in Greenland around the tenth century had agreed to pay taxes to the king about A.D. 1260. Greenland became a Danish colony in 1775 and was made a province of Denmark in 1953. In 1979, it was made an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, with a parliament and local control of health care, schools, and social services.

|

Students in Nunavut proudly hold up their Nunavut flag – we are visiting their school to ask them to partner with us in providing scientists with data and information they collect in the field! Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com. |

Nunavut, means “Our Land” in Inuktitut, the language of the Canadian Inuit.Just celebrating its 10th anniversary, this Canadian territory came to be in 1999 as a result of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which gives the Inuit title to about 20% of the land and resources in the new territory. More than 80% of the population in Nunavut (about 30,000 people) is Inuit, and Inuktitut is one of the three official languages of the territory.Explore Nunavut with GoNorth! Nunavut 2009 and the upcoming adventure learning expedition to Greenland February – May of 2010 at http://PolarHusky.com/explore. |

On June 21, 2009, the 30th anniversary of the establishment of home rule, a new referendum on Greenland’s autonomy took effect that paves the way for Greenland to eventually become independent from Denmark – maybe not in the very near future, but down the trail. Greenlanders are now recognized as a separate group of people under international law. The referendum makes Kalaallisut (Greenlandic) the sole official language of Greenland. Greenland will manage its own police force and the criminal justice system, as well as its own financing and natural resources. It is believed that much oil and oil revenues lie in the future of Greenland. The first 75 million kroner (US $13.1 million) will go to Greenland, and the remaining revenue will be split evenly with Denmark. In return Greenlanders will receive fewer Danish subsidies, which currently are about Dkr3.4 billion ($633 million), or about $11,000 per Greenlander, and account for about 30 percent of Greenland’s GDP. The primary industry in Greenland is fishing – export of shrimp in particular.

Greenlanders are now faced with the challenge of showing how to reconcile the development of the Arctic with its protection and to keep their traditional knowledge alive while merging its use with the tools and technologies of the modern world in ways that lead to financial prosperity. A challenge indeed! But one that comes with opportunities. The Inuit have survived in the Arctic environment only because of their exceptional ability to adapt to its brutal and hostile conditions and by developing a cultural framework that makes responsible use of very limited natural resources. Traditional knowledge, today as in the past, has much to offer in terms of its approach and perspective, especially when it comes to sustainable development and understanding climate change. To the Inuit and all Arctic peoples, the need for future sustainable development of natural resources and the realities of climate change do not have to be proven; it is a matter of how to respond and adapt accordingly. And the rest of the world is watching – to learn.

About GoNorth!

GoNorth! is a free adventure learning series for the K-12 classroom developed at the University of Minnesota. Each year February through May, GoNorth! goes live from a circumpolar Arctic locale on a journey anchored in a multidisciplinary K-12 curriculum aligned with national standards. Visit PolarHusky.com to learn more and join the team – it’s free!

Watch The Sub-zero Classroom and learn how adventure learning provides students opportunities to explore and learn with real- world issues!

This article was written by Mille Porsild. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright October 2009 – Story and images (c) by Mille Porsild, PolarHusky.com