When we think of the word “plants” we typically picture trees, bushes, grasses, and ferns – so-called “vascular plants” because of their full systems of leaves, stems, and roots. However, the plant kingdom also includes mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, simpler plants that lack these water-transporting structures.

Photos courtesy of Scott Kinmartin and Andrew Fogg via Flickr.

A defining characteristic of plants is their ability to produce energy through photosynthesis. Through this process, plants capture the sun’s energy and use it to fuel chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and energy-containing carbohydrates (sucrose, glucose, or starch).

Plants may reproduce sexually by flowering and producing seeds, or through spore production. They also reproduce asexually through budding, bulb formation, and other types of vegetative reproduction.

Even though most algae and fungi are no longer classified within the plant kingdom, they are often still included in discussions of plant life. Algae include microscopic, single-celled, and multicellular photosynthetic organisms such as seaweeds and green, red, and brown algae. They lack the structures that characterize vascular and nonvascular plants and are classified in the kingdom Protista.

Fungi do not produce energy through photosynthesis but instead obtain food by breaking down and absorbing surrounding materials. While previously classified with plants, fungi are now considered more similar to animals and are in a kingdom of their own.

Many fungi reproduce with fruiting bodies, a spore-bearing structure produced above soil or a food source. Mushrooms are a well-known example of fruiting bodies.

Lichens are a third group that, while often included in discussions of plants, is not classified in the plant kingdom. Lichens are a symbiotic association of a fungus and an alga. The fungus provides water and minerals from the growing surface, while the alga produces energy for both organisms through photosynthesis. Lichens compete with plants for sunlight, but their small size and slow growth allow them to thrive in places where plants have difficulty surviving.

Despite cold temperatures, permafrost, and short growing seasons, vascular and nonvascular plants, algae, fungi, and lichens are found in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Learn more about these hardy species and the adaptations that enable them to survive in such harsh environments.

ARCTIC PLANTS

Approximately 1,700 species of plants live on the Arctic tundra, including flowering plants, dwarf shrubs, herbs, grasses, mosses, and lichens. The tundra is characterized by permafrost, a layer of soil and partially decomposed organic matter that is frozen year-round. Only a thin layer of soil, called the active layer, thaws and refreezes each year. This makes shallow root systems a necessity and prevents larger plants such as trees from growing in the Arctic. (The cold climate and short growing season also prevent tree growth. Trees need a certain amount of days above 50 degrees F, 10 degrees C, to complete their annual growth cycle.)

Tundra vegetation is characterized by small plants (typically only centimeters tall) growing close together and close to the ground. A few of the many species include:

| Arctic willow A dwarf shrub that is food for caribou, musk oxen, and arctic hares. The Inuit people call it the “tongue plant” because of the shape of its leaves. |

|

| Pasque flower. This plant ranges throughout the northwestern United States and up to northern Alaska. Its covering of fine silky hairs provides insulation. |

|

| Bearberry.This low-growing evergreen’s leathery leaves and silky hairs provide protection from the cold and wind. The plant was named bearberry because bears like to eat its red berries. | |

| Purple saxifrage.This plant grows in a low, tight clump. It is one of the earliest plants to bloom. The tiny, purple, star-shaped flowers (1 cm wide) often can be seen above the melting snow. | |

| Arctic poppy.This plant is about 10-15 cm tall, with a single flower per stem. The flower heads follow the sun, and the cup-shaped petals help absorb solar energy. | |

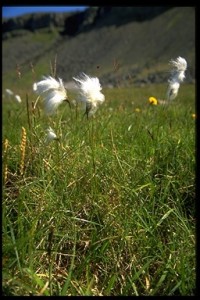

| Cottongrass.Named for its fluffy, white tufts, cottongrass is an important food source for migrating snow geese and caribou. |

Lichens grow in mats on the ground and on rocks across the Arctic. Lichens provide an important food source for caribou in the winter.

ANTARCTIC PLANTS

There are only two native vascular plants in Antarctica: Antarctic hair grass and Antarctic pearlwort. These species are found in small clumps near the shore of the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, where temperatures are milder and there is more precipitation.

There are approximately 300 types of moss found in colonies, over 300 nonmarine algae species, and approximately 150 species of lichens. Lichens can tolerate very cold temperatures, and thus can live where true plants cannot. Lack of water, not cold temperatures, is the largest concern, and lichens deal with this problem by living in cracks between rocks.

ADAPTATIONS FOR A POLAR ENVIRONMENT

Similar adaptations help plants, algae, fungi, and lichens survive in both the Arctic and Antarctic.

First, the size of plants and their structures make survival possible. Small plants and shallow root systems compensate for the thin layer of soil, and small leaves minimize the amount of water lost through the leaf surface.

Plants also grow close to the ground and to each other, a strategy that helps to resist the effects of cold weather and reduce damage caused by wind-blown snow and ice particles. Fuzzy coverings on stems, leaves, and buds and woolly seed covers provide additional protection from the wind.

Plants have also adapted to the long winters and short, intense polar summers. Many Arctic species can grow under a layer of snow, and virtually all polar plants are able to photosynthesize in extremely cold temperatures. During the short polar summer, plants use the long hours of sunlight to quickly develop and produce flowers and seeds. Flowers of some plants are cup-shaped and direct the sun’s rays toward the center of the flower. Dark-colored plants absorb more of the sun’s energy.

In addition, many species are perennials, growing and blooming during the summer, dying back in the winter, and returning the following spring from their root-stock. This allows the plants to direct less energy into seed production. Some species do not produce seeds at all, reproducing asexually through root growth.

ADAPTING TO A CHANGING CLIMATE

The polar regions have been of great concern as the Earth’s climate warms. While we’ve heard about the declining sea ice and its negative impact on marine wildlife, there’s evidence to suggest that Arctic plants may be better able to adapt to a warming world. Studies of nine flowering plant species from Svalbard, Norway, suggest that Arctic plants are able to shift long distances (via wind, floating sea ice, and birds) and follow the climate conditions for which they are best adapted. Wide dispersal of seeds and plant fragments might ensure survival of species as climate conditions change. While encouraging, this data does not necessarily extend to Antarctic species or species in the temperate regions.

LINKS

Tundra Plants

Detailed information about eight plant species that are found on the Arctic tundra.

Plants of Antarctica

An overview of the species found in Antarctica.

Life on Antarctica: Plants

Information about the vascular plants, lichens, mosses, algae, and fungi found in Antarctica.

Grow Low, Grow Fast, Hold On!

An overview of Arctic plant adaptations.

Arctic Plants Have Adjusted to Climate Changes

Blowing in the Wind: Arctic Plants Move Fast as Climate Changes

These two articles discuss findings related to Arctic plant mobility and resiliency.

NATIONAL SCIENCE EDUCATION STANDARDS: SCIENCE CONTENT STANDARDS

The entire National Science Education Standards document can be read online or downloaded for free from the National Academies Press web site. The following excerpt was taken from Chapter 6.

A study of plants aligns with the Life Science content standards of the National Science Education Standards. In grades K-4, students focus on the characteristics and life cycles of organisms and the way in which organisms live in their environments. Students in grades 5-8 expand on this understanding by focusing on populations, communities of species, and the ways they interact with each other and with their environment.

Teaching about plants can meet a wide variety of fundamental concepts and principles, including:

K-4 Life Science

- The Characteristics of Organisms

- Life Cycles of Organisms

- Organisms and Their Environments

5-8 Life Science

- Reproduction and Heredity

- Regulation and Behavior

- Populations and Ecosystems

- Diversity and Adaptations of Organisms

This article was written by Jessica Fries-Gaither. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright March 2009 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.