Natural resources are materials derived from nature that provide value in meeting the needs of people. These materials can range from basic elements of the earth such as water, minerals, timber, and soil to products originating from fossil fuels, such as petroleum oil, natural gas, and coal.

RENEWABLE VERSUS NONRENEWABLE RESOURCES

George Brimhall, geology professor at the University of California at Berkeley, uses the idea of “recharging time periods,” i.e., the period it takes to replenish a resource, to determine if a resource is renewable or nonrenewable. Among energy sources, hydroelectric, solar, and wind are deemed renewable since they are replenished in a short amount of time. Because fossil fuels take a long time to replenish, they are considered nonrenewable.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), over 85 percent of all energy use in the United States can be attributed to three nonrenewable resources – oil, gas, and coal. Eight percent of energy consumption comes from nuclear power. Renewable energy sources (hydroelectric, solar, geothermal, wind, biomass) make up 7 percent of total use. Collectively, this energy consumption can be categorized into four main sectors: industry, transportation, residential and commercial, and electricity.

Locally, where does your energy come from? The EIA site has energy information for each state so that you and your students can find the answer to that question.

Related Online Resources

Fossil Energy: How Fossil Fuels Were Formed

This one-page, illustrated article describes the formation of fossil fuels. There are links to more information about three specific fuels – coal, oil and gas. This web site is included in the NSDL K-6 Science Refreshers collection.

Energy Kid’s Page

This site contains background information, a history of energy, activities for grades K-7, and games. It was developed by the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

NREL is the nation’s center for renewable energy research and technology. The laboratory offers basic information on renewable energy sources, professional development programs for teachers (including summer internships at the lab), and student resources at the high school and college level.

NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE POLAR REGIONS

Tapping into the fragile ecosystems of the polar regions for natural resources is a controversial issue. There are no simple solutions but many different perspectives from around the globe. Climate change, diminishing fossil fuel reserves, increasing greenhouse gas emissions, rising gas prices, dramatic changes in world supply/demand, and the greater need for global cooperation all play a part in this complicated puzzle. The poles are at the center of many of these issues.

Resources of the Arctic

Warmer temperatures in the region and melting sea ice have made it easier to extract resources from more sections of the Arctic. As a consequence, the Arctic’s role in resource acquisition and management will continue to grow in the decades ahead, especially for the nations that border the Arctic Circle.

The Alyeska Pipeline transports over 2 million barrels of oil a day from fields in northern Alaska. Since it went into operation in 1977, the pipeline has transported over 15 billion barrels. This August, the Alaskan legislature approved the creation of the Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline, paralleling the oil pipeline south to Fairbanks and cutting through Canada to connect to existing natural gas lines. Completion is expected in 2018. This new project will undoubtedly be closely scrutinized as the tension between environmental concerns and the ever-increasing need for energy sources rages on.

Other recent events have brought the Arctic further into the spotlight. ScienceDaily cited a recent U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) report assessing the amount of petroleum resources available in the Arctic Circle region:

The area north of the Arctic Circle has an estimated 90 billion barrels of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil, 1,670 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of technically recoverable natural gas liquids in 25 geologically defined areas thought to have potential for petroleum.

The USGS report estimates that significant amounts of oil and natural gas resources can be found in Arctic Alaska, East Barents Basins (an off-shore area near Russia), Amerasia Basin and other sections of the region identified in the map below.

Image source: USGS, http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3049/fs2008-3049.pdf

While reports indicate the vast oil and gas reserves available in some areas of the Arctic, groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council are concerned that drilling could open the doors for extracting other natural resources, such as timber and minerals, in these areas as well as protected areas. A particularly debated area, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northern Alaska, is home to over 240 different species of wildlife.

Recently, Russia took steps to explore and protect its natural resource interests in the Arctic with an increased military presence and the approval of government sanctioned companies to develop oil reserves. As climate change melts sea ice and opens more passageways into the Arctic Ocean, Russia may take the lead in oil exploration and extraction. Presently, Russia is the leading producer of nickel, with mining operations in copper, cobalt, and other minerals in northern regions of the country.

While changes continue in the Arctic, the European Union (EU) has responded to climate change by taking ambitious steps to increase the use of renewable energies by 20 percent by the year 2020. Northern countries such as Denmark, leader in wind power production in the EU, and Norway, a leader in solar energy technology, will play a significant role in this effort. From inflatable solar panels to harnessing human body heat for a railway station in Stockholm, some of the most interesting innovations in renewable energy can be found in Europe, as seen in these pictures from Forbes.com.

Related Online Resources

USGS Podcast on the Arctic Assessment Report

A brief interview with two U.S. Geological Survey scientists on the report. Other podcasts are available at http://www.usgs.gov/podcasts/.

Arctic Circle

A collaborative effort through the University of Connecticut, this web site addresses environmental issues of the Arctic from the perspectives of natural resources, history and culture, and social equity and environmental justice.

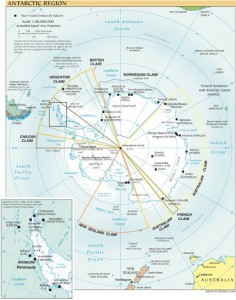

RESOURCES IN ANTARCTICA AND THE ANTARCTIC TREATY

Like the Arctic’s resources, Antarctica’s natural resources are on the radar from both environmental- and energy-related perspectives. In 1959, the Antarctic Treaty was signed by 12 countries to ensure that Antarctica remained a war-free land, protected with provisions for conserving and preserving the environment and international scientific research.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency Factbook.

The treaty’s success is evidenced by 34 countries joining the first 12 as members and passage of provisions to protect seals (1972), to conserve Antarctic marine living resources (1982), and to uphold an agreed protocol for environmental protection (1991). The protocol, known as the Madrid Protocol, stipulates a moratorium on mining in Antarctica for 50 years. Given the continent’s stores of coal, natural gas, oil, and minerals, the Madrid Protocol recognized the need for strongly defined measures beyond the original treaty and was finally approved collectively by treaty nations in 1998. The moratorium will come up for review in 2048.

Australia’s territories claim 42 percent of the Antarctic, making them a key player in the continent’s future. A part of the country’s Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, the Australian Antarctic Division is well aware of the impact humans have had on Antarctica. It shares with other countries its concerns about tourism, insufficient waste disposal, and use of nonrenewable energy sources by the science stations on the continent – counter to environmental measures defined in the Antarctic Treaty. As a result, Australia has stepped up its use of renewable energy alternatives to run its operations.

Capitalizing on the strong winds of the Antarctic, Australia has installed wind turbines at its research stations. In 2006, Australia’s Mawson station became the first station in Antarctica to utilize wind turbines to collect hydrogen as an energy source. The energy generated by wind turbines is used to electrolyze, or split, water into its components of hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen is then stored under high pressure as an energy source that can be used even in colder months when fossil fuel is less accessible.

Belgium has also responded to the need for alternative fuel sources by creating the first zero emissions Antarctic science station, completely supported by renewable energy.

Undoubtedly, our global future both in terms of energy and environmental sustainability will be strongly tied to the future of the poles.

Related Online Resource

Australian Antarctic Division

This site has background information on Antarctica and on Australia’s science stations.

This article was written by Robert Payo. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle, Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright October 2008 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.