In the 1986 film Little Shop of Horrors, a pathetic shopkeeper is saddled with a demanding houseplant from outer space. The plant, named Audrey II, turns out to have a disturbing taste for nonvegetarian fare. She reminded me of the scary-looking Venus Flytrap plants that some of us, as children, attempted to keep alive with houseflies.

The idea that plants can have uncharacteristic cravings for animal protein puts them in a category somewhere between organisms that are nourished by rainwater and minerals and those that would prefer a burger and flies. For example, at http://mycarnivore.com/ four varieties of flesh-eating plants, from among 600 varieties of carnivorous plants, are sold as “pets” in something called a “cage/terrarium” with “bedding.” These terms imply that a plant might get up and self-transplant if the food supply was not to its liking, although my Venus Flytrap never moved from its pot over the kitchen sink and seemed friendly enough.

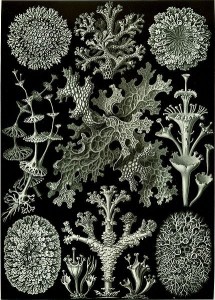

The most prevalent, versatile and mysterious plantlike organism in the Arctic and Antarctic is a lichen, a slow-growing hybrid able to withstand extreme heat and cold. Lichens do not need soil to live, are often colorful, and are an important food source for Arctic animals such as caribou. Lichens grow on rocks as scaly, dry-looking growths, although they can also be found as small bushes and in trees. There are approximately 2,000 varieties of Arctic lichens compared with only 200 Antarctic varieties.

Enthusiasts are forced to admit, however, that, like Audrey II, lichens are not real plants. Lichens result when a complex relationship is forged between an alga and a fungus — a fungus takes over an alga. While lichens have traditionally been considered an example of a symbiotic relationship in which the alga produces food and the fungus provides protection, some scientists have questioned whether this relationship is truly mutually beneficial.

Those who question the mutual benefits have called lichen a “living prison cell.” The algae is held prisoner of the fungus and produces the food for the lichen. Biologists call this relationship “controlled parasitism.”

To see how a chance meeting between a fungus and an alga might turn out, visit Lichenland from Oregon State University: http://ocid.nacse.org/lichenland/html/meeting.html.

While scientists still debate the exact nature of the relationship between a lichen’s fungus and alga, the combination allows them to survive in some of nature’s harshest environments.

This article was written by Carol Minton Morris. For more information, see the Contributors page. Email Carol at beyondpenguins@msteacher.org.

Copyright March 2009 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license.